Story for the Day: Mercenaries and Marinas - Part 3

They turned toward the table, where

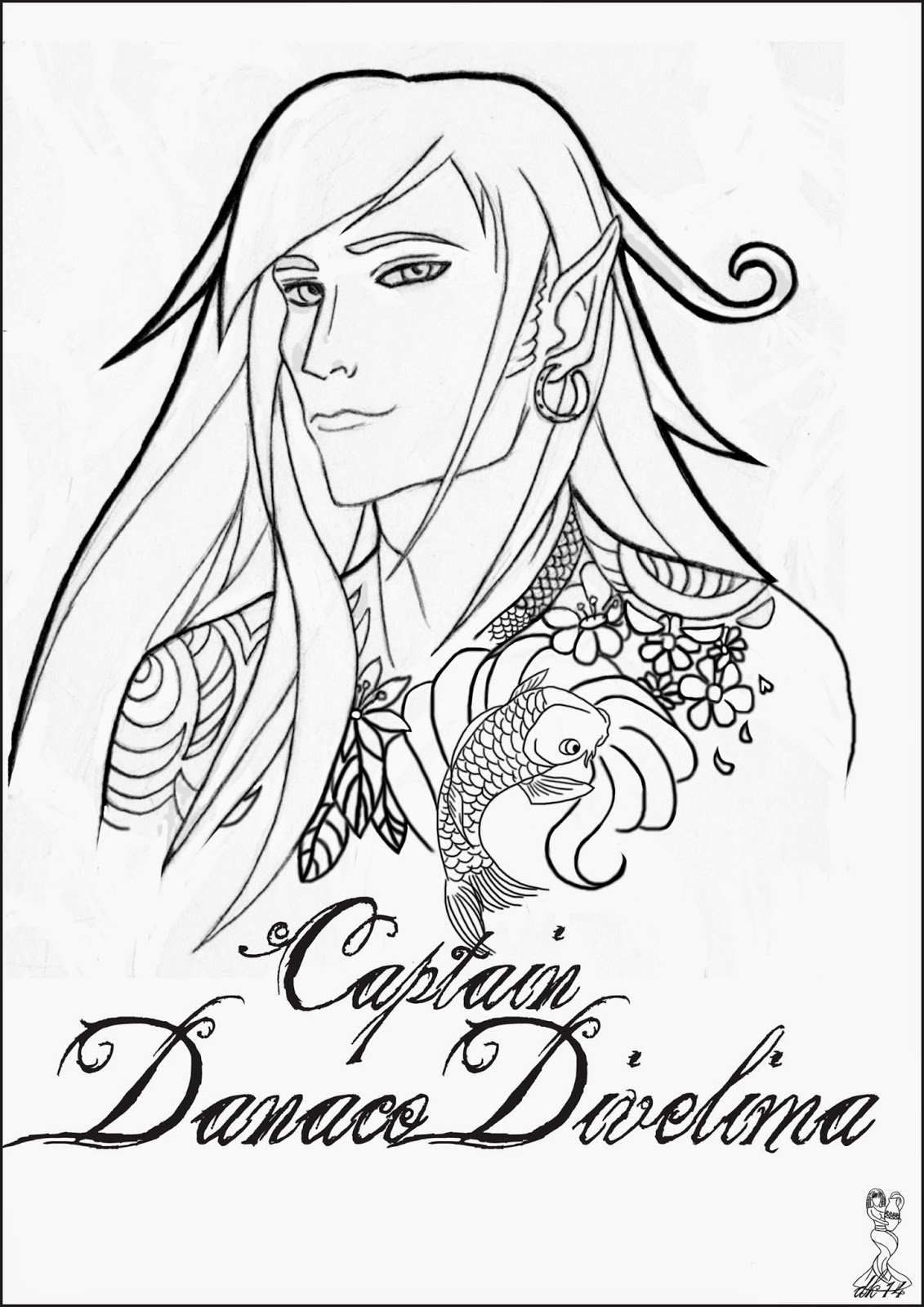

Danaco stood amongst the children, mantling over the

table and folding

something over itself. They conspired in a confederacy of whispers, the

symphony of susurrations drowning out what was being discussed, and when Danaco

finished his folding, he righted himself and held up a small paper ship.

“There is your Galleisian fluyt,”

Danaco pronounced, holding the ship to the light. “So much for your complaints

that the Galleisians were egregiously underrepresented. Well, now we have our

ship, but she must have a name and a berth. What shall we call her?”

“How about the Marghilesse?” said

Dorrin.

“Aye,” Little Jaicobh chimed. “My

ma’d like bein’ a ship.”

“Named after your mother, is it?”

said Danaco, with the fondest smile.

“Aye, so!”

“I am very sure she thanks you. It

is not every day that a woman has the chance of being named after a such a

glorious vessel. Come,” holding the paper ship to the children’s level, “where

shall we put her? She has no use of a name if she has no place to put her

moorings.”

“In Erieanneann,” said Soledhan,

stabbing his finger at board.

“But does your annex have a port?

Well, there is an estuary there, I perceive, and as we have built a ship, why

should not we build a port? Go on, take it and place it there, and then we

shall take her out for her maiden voyage.”

“Mr Captain Danaco sir?” said

Little Jaicobh.

“By Myrellenos, so many tender

appellations! How they do grow every time you address me. Do call me captain,

if you must call me anything that is not Unpalo.”

Soledhan’s nose scrunched. “The

Lucentian word for uncle?”

“Well, you are relations, are not

you? Houghleidh is rather a son to me, and Cabhrin by association a grandson. I

am old enough to be your grandfather twice over, though I do not look it by

Frewyn or Marridon standards—and why should not you call me Unpalo? You see me

often enough to be familiar with me, and you have other Lucentian and

Marridonian cousins, though they are not by blood-- which means just nothing at

all—and why should I not be considered an uncle?”

“Aye, Captain Unpalo sir,” said

Little Jaicobh, with a hearty salute.

Danaco’s heart warmed at such

eagerness. “Captain Unpalo, you say?”

“Well, you have to be a captain if

you got a ship and all.”

“Quite so. Very well, Captain

Unpalo it is-- but no sirs, I entreat, my darling. Sirs should be reserved for

those whom we do not like and are to be used when we wish to pretend that we

do. Civility at length does go a long way, especially when apologizing for

having to take the toes of one who has wronged you.”

“Can we take a few toes?” Soledhan

beamed.

“I daresay your mother would object

to my teaching you any such thing, and were she not listening, which she most

assuredly ought to be, as mothers can hear the secrets of their children

through walls, I should teach you all I know about dismemberment and its many

uses if your mother and tutors not disclaim.”

“Aw.”

“Disappointment excites passion, my

child,” the captain crooned, “and where you are disappointed now, you shall be

rewarded a hundred times by the zeal your frustration rouses. Be ardent as you

ought, and you shall never be disappointed long.”

“Does that mean you’ll teach us how

to take toes eventually, captain?” asked Dorrin.

“Well, we all do grow older,” was

Danaco’s sagacious answer, “and you need not wait long to accomplish that.” He

exchanged a smile with Hathanta and Baronous, who were smiling to themselves

and standing close by, and then placed the paper ship onto the board. “Now, who

should like to give the Marghilesse her due? Jaicobh, as His Highness has

incurred the honour of naming her, I believe the honour of releasing her to sea

is yours.”

The children clamoured about him,

ready to move their ships and follow wherever the HRH Marghilesse should take

them, and the adults in the library looked on, observing the continuance of the

game with devoted aspects.

“It always astounds me that

children have no idea of fame and legend,” said Alasdair quietly. “There is the

greatest literary marvel of our time, standing and playing games with them, and

they only see a man who wants to befriend them and blow their ship out of the

water with pirates.”

“I think they understand his

majesty, Alasdair,” said Boudicca, “merely due to your infatuation about him or

even Vyrdin and Brigdan’s reverence of him, but I think their innocence keeps delightfully

unaware of his grandeur. He is a lord, he is the servant of Lamir, he has

reconquered his country from false kings and saved it from tyranny, he

vanquished countless pirates, marauded ships of their greatest treasures, he

has become captain of the Lucentian royal guard, was a guildlord before Ladrei

was—his accomplishments alone should garner anyone’s veneration, but he is so

revoltingly dashing, especially for his age, with that mane of his and his

excellent taste in dress, that he will make even the most distinguished of

kings welter in disdain for him.”

Alasdair spied the captain’s silken

hair and embroidered waistcoat, and made as slight a hum as he could.

“And he is so wretchedly good with

the children.”

“Yes, he is very good with them.”

“And he is such a gentleman every

lady that passes his way, treating every one of them as if they were a queen.”

Alasdair could not but know that he

was being provoked, but he turned to the commander anyway, to scowl and glare

and catch her subrisive aspect before averted his eyes and flouting to himself.

“Danaco Divelima might be many

things,” the commander continued, “but he does not look half so handsome as you

do when you pout.”

“I’m not pouting,” Alasdair

asserted, trying not to flout and look sullen.

“What? Is that all your defense?

Alasdair, you can contend far better than that.”

There was a pause, Boudicca smirking to

herself and Alasdair glowering at the corner of the room, and then Alasdair,

unable to help himself, amended with, “It isn’t fair to compare me with one of

the greatest men in the world. Anyone would look inferior by comparison. It’s

like trying to compare me with my grandfather.”

“You do His Late Majesty immense

credit.”

It was Danaco who had attested to

Alasdair’s merits, and it was said with such unanswerable dignity that for a

few moments there was no other sound in the room beyond the quiet murmurations

of the children. The severe stares, the dignified expression, the defiant

manner recommended the captain’s decidedness; he was not to be gainsaid, and so

artless and ingenuous was his character that Alasdair turned away, divided

between embarrassment and happy humility.

Enjoy the new stories? Help us fund the next novella on our Patreon page HERE!

Comments

Post a Comment