Story for the Day: Gearrog Revisits

Gearrog the Brickmaker is a famous brick and tile maker from a small town in northeastern Westren. He's known in Westren as a master builder, but to the kingdom, and especially to the castle keep, he is known as Vyrdin's saviour. He was the man who reported and testified against Carrighan, the man who made himself Vyrdin's tormentor before Vyrdin came to the keep, and while Gearrog was well-rewarded for his honesty and bravery in coming forward and saving Vyrdin's young life, he still tends his kilns and returns home to Westren for the autmn hunts when he can:

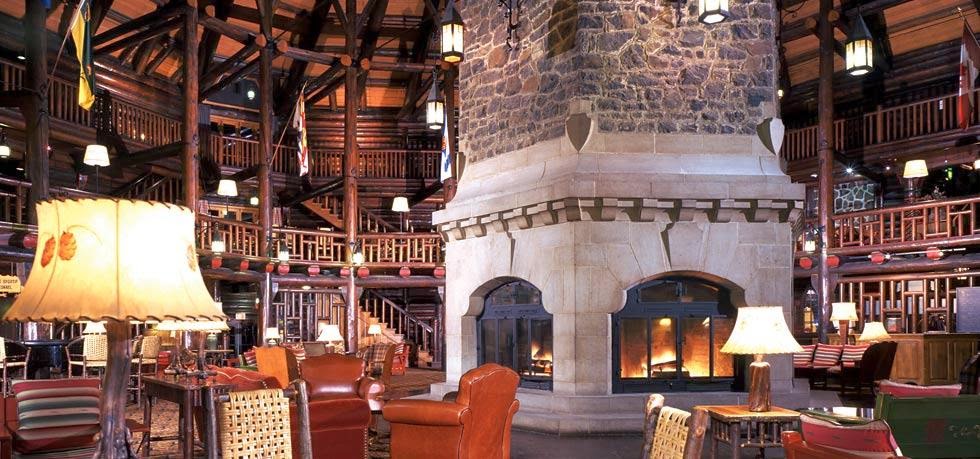

never thought this place would look like thess. Ah never thought there’d be o’ thess glass. From the outside—well, from where we were standin’—the lodge looks liek it’s maed from brick and stone.”

never thought this place would look like thess. Ah never thought there’d be o’ thess glass. From the outside—well, from where we were standin’—the lodge looks liek it’s maed from brick and stone.”

“Aye,”

said Bhaunbher, in a thrill of wonder. “Ah didnae think this place would be

known for its craftsmanship. Ah thought it was just gonna be another huntin’

lodge, with skins and pelts everywhere and o’ that. This is amazin’-- but how

does the glass keep in o’ the heat in the winter? True there’s a grand fire in

the middle, but near the windows, it must be cold.”

“Cold?”

Edmahrid exclaimed, in laughing astonishment. “You speak like an old maid

instead of a fearsome hunter, lad. Here you worry about cold when we must go

out and hunt in all weather.”

“Aye,

we dae, but what about o’ these visitors and workers? What about the wee-uns?

There are swarms o’ ‘em. Ah didnae thenk there’d be so manae at a huntin’

lodge.”

“For

some of them, the lodge is their home, lad. For others, it is where their

parents work, and they join them here for an education in the chapel instead of

attending lessons in the town, where they might spend the better part of their

day without the company of their mothers and fathers. Other children are

frequent visitors, coming with their families from the neaby towns. Their

parents watch the hunt and support the local tradesmen, and the children use

their time here as a holiday—it nearly is a holiday for the entire villiage.

Vendors bring all their wares here for the trading pavilion, musicians travel

here to entertain, and even some of the dancers from Hallanys come when they

can, to promote themselves and to take in all the regalia. You need not worry

about the cold or the children, lad. There is always something to occpy them,

for if they are not being looked after by the Brother, they are attacking the

caramel apple cart or racing each other through the field, or trying to ride

the boar or betting which one of them will be able to milk the goats. Believe

me, lad, as one who is often here, I tell you they are busy kept and always

warm when there is a fire on. There are pelts aplenty for them to hide under,

and many of them will willingly stand beside the oven if it means Deana will

offer them bolaig enough to feed a bear.”

Bhaunbher grimaced and looked doubtful. “We liek

it well enough, but Ah doant thenk a bear-bear would eat it. The smell o’ it

cookin’ might repell ‘em.”

“Aye,”

said Bhaunbher. “Dirrald and Ah were cookin’ it once when we were first

stationed in the mountains, and the smell aff it near killed yin o’ the brown

bears lurkin’ the area.”

“It

did. We watched hem comin’ toward us, and when Bhaunbher took the lid from the

pot, the smoke rose up and carried over the mountain side, and when it reached

hem, he reared and ran. He as onlae a cub, but Ah thenk we offended his ideas

o’ eatin’.”

Eadmhaird

laughed heartily and shook his head. “Bolaig is enough to fill any stomach and

offend any tongue. I had never eaten it until I came to the Westren. I admit to

not being fond of it at first, but when the snow came to the mountains, I ate

more of it than I ever thought I should. A hard working man hungry enough will

eat anything which promises to fill him, lad—“ here was a sly smile, “--which

would explain the west’s unnatural love for mardeam. All the farmers,

horse breeders, artisans and craftsmen in the kingdom must be poor enough and

hardy enough to eat something that tastes like salted tar—Isn’t that so,

Gearrog?”

Eadmhaird

turned, and just approaching from the corridor was Gearrog, emerging from the

teeming crowds with all his usual good nature and hale self-determination.

“Aye,

no denyin’ it,” said he, thrusting his hand forth and clasping Eadmhaird’s,

giving it a stout shake, “mardeam tastes like the wrong end o’ the sardine

barrel, but it’s good for ye. That’ll put the hair on ye, though—“ eyeing

Dirrald and Bhaunbher, “don’t think yous lads need anymore than what yous got.

Lucky for yous lads all that hair’s just yer arms. Yous lads don’t got a big

ol’ wheat stalk sproutin’ up from yer chest like some o’ these walkin round

here.”

He

nodded toward Eadmhaird, glanced cautiously at the top of his chest, where sprouted

a dark and brambled tuft, and Gearrog

winked at him and gave his back a hardy slap, and Eadmhaird returned the

sentiment, patting Gearrog’s shoulder with the same if not more generous

affection.

“Glad to see you, Gearrog,” said

Eadmhaird, in a kindly hue. “Glad to see you anywhere that is not beside your

kilns.”

“Aye,” said Gearrog, with an

amorous sigh, “Rough workin’ the kilns, so it is, but it’s where I love to be

masel’—and someone’s gotta be makin’ all these bricks here anyway.”

“Ye repair the lodge?” asked

Bhaunbher.

Gearrog shrugged. “Someone’s gotta.

I put in all this new brick here in the entrance just last year. Took me the

while to get all the mortar in the archway just right, but,” with a pout of

proud conviction, “she’s is holdin’ up right well an’ some.”

“And you have not been here since

then,” said Eadmhaird archly, the glint in his eye dancing about. “What do you

do in your Farriage workshop that requires to much attention you cannot visit

your home oftener? They have no need of your bricks and tiles in the east as we

do.”

“Aye, well, sure they don’t have as

many brick buildin’s and houses like we do here in the west, but eastern folk sure

do know how to break things easier. I’m not hurtin’ for business, mind—folk

just stopped breakin’ things. Only took ‘em Gods know how long. I like workin’

as much as the next workin’ lad, but there ain’t bolaig enough in the east to

keep me goin’ half so long durin’ the eastern winters: they’re wetter, they’re

colder—they’re colder ‘cause they’re wetter—and can’t get anyone to make a

decent bolaig out there. They’re always leavin’ out all the best parts, like

the sheep livers and pork lard. Glad to be in this here lodge— the place

smelled o’ bolaig comin’ up to it. Near ran the last stretch of the way just to

have first batch of what the cook was takin’ out o’ the fire.” He closed his

eyes, inhaled, and gave a prolonged and gratified exhalation. “Yous lads smell

that? That’s the smell o’ Westren, that is. Growin’ up in Hathleidh, that’s

anybody ever had, bein’ a village of labourin’ lads.”

“So is that why you’ve decided to

visit? Was there no bolaig left in the east?“

Gearrog tapered his gaze, and Eadmhaird simpered to himself.

“Finally a break in the work,” was Gearrog’s

kind answer. “Finished my last order near two week ago. I says I gotta get home

before somebody come and ask me for somethin’ so’s I can enjoy my holiday this

year. I was hopin’ to beat the first snow, and hasn’t snowed yet. Had a bit o’

frost, but nothin’ to worry by, nothin’ I can’t travel on. Stayin’ here for the

hunt, then goin’ northeast to see the ol’ home. Might be there the while so’s I

can do what repairs need doin’ on the house. Yous two lads wanna bring yer

kills there, I’ll fire up the kiln and put the potatoes and butter on the

spade.”

Dirrald and Bhaunbher glanced

charily at one another.

“Ach, don’t worry yerselves, lads,”

said Gearrog, waving a hand at them. “We brickmakers cook everythin’ in the

kiln. It’s as sanitary as yous lasds cold want. I says when I gotta stay by the

kiln for days on end, there ain’t no time to be goin’ back and forth to the

house, doin’ the cookin’, mindin’ the stove when I got a kiln to tend.”

“There would be, if you had someone

to live with you,” said Eadmhaird.

Gearrog’s face floddered, and he

chuffed, waving the hunter off. “Go on way outta that now, “ and then turning

to Dirrald and Bhaunbher, “always gotta make it about bein’ unattached. You

ain’t attached to nothin’.”

“And so I hope not to be for a long

time coming. I am still far too young for that.”

Gearrog gave a dry laugh. “Ha!” he

rasped, “Talkin’ all confused now. Yer older than me. Ye might like that

autonomy ye got, but can’t say I know any man or women who’d stand the smell

aff ye when yer covered in deer fewmets.”

“The animals don’t mind it,” was

all Eadmhaird’s defense. “And while they do not assist me in making dinner,

they are dinner in one form or another.”

“Well, I got my shovel and my kiln for

cookin’. Yous two lads ever had bacon and eggs from the kiln?”

Dirrald and Bhaunbher shook their

heads and seemed suspicious.

“Ach, brigade-folk don’t know

what’s good. What’re yous lads learnin’ up in the mountains? Not how to cook

right, I says. Yous lads gotta learn efficiency. If yous had a kiln up there—“

Here Eadmhaird stared at the ceiling, silently pining over how Gearrog would be

led to talk of kilns and brickmaking if asked, “--If yous got a kiln, yous lads

got everythin’ yous’re gonna need: yous got heat, yous got a stove, and yous

got a light source what can be covered—and if yer after a bit o’ craic, yous

can bring some apples to the boil and harvest a steam cider outta it. Yous just

build a kiln from straw and mud, light it, and put yer bolaig or what it is yer

wantin’ on a clean shovel, and once that kiln’s burnin’ at full heat, yer bolaig’ll

come out roasted. Send the whole mountainside full o’ bears runnin’ away from

yous. Well, Borras, I’d go on, but I see the eyes startin’ to go. Ach, it can’t

be helped for nothin’. I been at my kilns so long--”

“That your desire for variety has

dragged you away from them at last…” Eadmhaird interposed. He paused and looked

sagacious. “With true affection for your profession, I wonder that you can be

here so long. You come for the hunts, but you must stay for someone if you mean

to be torn from your beloved furnace.”

Gearrog scoffed and folded his arms. “Aye, have it,”

he humphed. “G’on, geez it a go and let it all out, pointin’ the finger at me

and takin’ the craic out o’ me when ye ain’t got no one yerself. Been just fine

these years with nary a trouble and I don’t go lookin’ for none neither, if ye

folla me. I life mahsel’ as mahsel’, so I do, don’t mind tellin’ ye. Don’t mind

if this lodge was meant as a meetin’ place for all the hoghmagandy in the west.

I says I’ll have none of it, and shise

shin, so I won’t. I’ll leave it to yous lads,” nodding toward Bhaunbher and

Dirrald. “Sure ‘em pelts yous lads got there’ll attach a few minnows to yer

lines.”

Dirrald looked as though he had

little idea what the brickmaker meant. “Hoghmagandy?”

“Sure.” Gearrog glanced at the

balcony above them. “Every hunter in the kingdom comes here for a bit o’ craic

before the hunt—and after the hunt too, the afters probably to make ‘emselves

feel better for losin’ to Eadmhaird. There are a hundred rooms in this here

lodge, not all of ‘em lived in. What yous think all ‘em rooms are for?” He

quirked a brow. “Hunters sleep outside when they don’t got company, if yous

lads folla me.”

He pointed to the railing above,

where stood four young couple, the men seasoned hunters, with their hulking

pelts, dark complexions, and defined forms, and the women, their eyes bright

and smiles still brighter, reveling in the close conversancy that such

familiarity afforded: a delicate touch, a sobering glare, a whispered

vulgarity—these were what charmed their few moments away from the great hall

and brought them into a hunter’s arms. Dirrald and Bhaunbher looked and looked

away, their complexions crimsoning over as they spied vales being fondled,

napes being caressed, parted lips looming close to one another.

Comments

Post a Comment