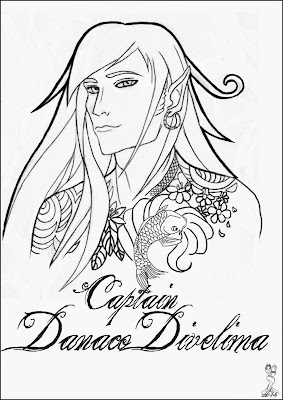

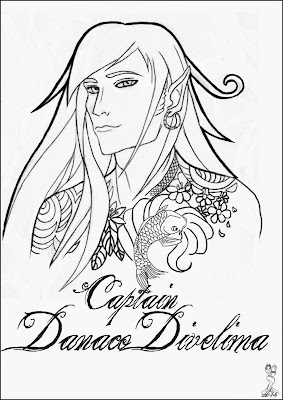

Story of the Day: The Lady Tabytha Ardalyddes

Many wonder what sort of lady it is-- or lord, for that matter-- that can attach Captain Danaco's heart, and while he might have many a dalliance, there is only one who has succeeded in capturing his perfect attention: The Lady Tabytha Ardalyddes, Matron of the Cipher:

A gale drifted in from the neighbouring harbour to

complement the rising tide, and the saline intimation of the sea roused lilted

over the balcony, rousing the matron from a gentle sloom. She sat

up on the

bed, her legs swathed in silk sheets, her pinned hair disheveled and deflated,

one side of her face warm and wrinkled whence pillows had pressed against it, and

she had time for one oscitation before consciousness revived what the throes of

violent passion had so lately exhausted. She hemmed and rubbed her eyes, her

features illuminated by the subdued light pervading the balcony window. She had

been only asleep a few moments, but the sight of sideboard already furnished

with high tea, and the glimmer of moonlight casting its lunanata along the far

far, made her believe she had been longer out than she really was. Curls of

steam billowed up from the teapot, the water and wine had already been mixed,

and the butter on the warm scones had begun melting.

A gale drifted in from the neighbouring harbour to

complement the rising tide, and the saline intimation of the sea roused lilted

over the balcony, rousing the matron from a gentle sloom. She sat

up on the

bed, her legs swathed in silk sheets, her pinned hair disheveled and deflated,

one side of her face warm and wrinkled whence pillows had pressed against it, and

she had time for one oscitation before consciousness revived what the throes of

violent passion had so lately exhausted. She hemmed and rubbed her eyes, her

features illuminated by the subdued light pervading the balcony window. She had

been only asleep a few moments, but the sight of sideboard already furnished

with high tea, and the glimmer of moonlight casting its lunanata along the far

far, made her believe she had been longer out than she really was. Curls of

steam billowed up from the teapot, the water and wine had already been mixed,

and the butter on the warm scones had begun melting.

A gale drifted in from the neighbouring harbour to

complement the rising tide, and the saline intimation of the sea roused lilted

over the balcony, rousing the matron from a gentle sloom. She sat

A gale drifted in from the neighbouring harbour to

complement the rising tide, and the saline intimation of the sea roused lilted

over the balcony, rousing the matron from a gentle sloom. She sat

“Hollie

came in,” said a voice beside her.

A hand

smoothed over her thigh, and she turned to find Captain Danaco lying at her

side, lounging with his legs draped over the side of the bed, his head

supported by the bedrest, the amber glow of the setting sun painted across his

chest. A satisfied smile wreathed his lips, the carps garlanding his arms

undulated as he flexed, he widened the space between his legs, and he gave her

thigh an affectionate press.

“Milado,”

she laughed, looking down at his full form.

He

pressed his hips forward and gave himself a suggestive look. “I know seeing me altogether is always a treat. Do not I

look well by twilight?”

The

matron shook her head and blushed in spite of herself. “You are positively

incorrigible.”

“Do say

so, inpala. Were I not debauch and irredeemable, I should have been exiled for

nothing at all.”

“I forget the terms of your

banishment far too often.” She leaned forward, the tip of her nose meeting his.

“Did you at least cover yourself when Hollie came in?”

“You

dare ask me to cover something so exceptional as this?” said he, bending a knee

and gesturing to his whole extent. “Am I not impeccable? I do work on myself

tirelessly. No one should be spared from the result, not even Hollie.”

The

matron’s eyes crinkled with smile lines. “How you will make a manstress of yourself,

milado. Only imagine my position.”

“I

daresay I do imagine your position a great deal, inpala. I saw it only half an

hour ago.” Danaco drew his fingertips along her lower back, tracing the outline

of her hips. “You make a monstrous pretty shape when you are bent before me.”

Here

was a salacious look, and it was shared and blushed over and deliciated in, and

though the matron turned aside, to regale in shameless iniquity and secret away

a grin, she pressed the captain’s hand and held it to his heart.

“How

you will flatter me, milado,” said the matron, turning back, “but did you really

not cover yourself when Hollie came in?”

“Indeed,

I had no reason to shield her, inpala. Her eyes were turned toward the wall the

whole time. She is such a timid creature, and she is so mindful of her

mistress’ privacy that she is all hemlock when I am with you. Would that I had

a dozen such on my ship.”

“That

would be and unnecessary indulgence to you, milado, and we know you are never

addicted to indulgences.”

With

gentle alacrity, Danaco clasped her wrists and drew her down, laying her breast

against his. “I am when you are my indulgence,” he purred, touching his nose to

hers.

He grazed

her cheek with the back of his hand, drawing a drape of boltered wisps away

from her face, and while eyes met and spirits regaled the redemancy of elated

hearts, other sentiments soon prevailed. A gravity soon appeared, each

remarking the other with a sobering aspect, and the knowledge of what must be

beleaguered them both.

“Evening

is coming on,” said Danaco presently, holding her hand over his heart.

She

made no answer, and the captain pressed her fingers to his lips, watching the solemn

feelings of what gloaming must bring surmount her. Her gaze faltered, her voice

and courage failed her, and the hand that cradled her chin and passed his thumb

along the promontory of her cheek only made her more melancholy.

“Would

that you come with me, milada ina,”

Danaco dutifully implored. “I should make you my maiden of the seas, and you

should stand with me, with your hand at the helm and the coarse sea breezing

tumbling your hair -- but you are too much a woman of the world to be confined

to a ship, and while I would have you at my side, at my table, and in my bed

evey evening, while I would climb the rigging to the nest to bring you feathers

from passing falcons and tie myself to the keel to bring you pearls from the

mouths of mollusks, you naturally belong to this house and everyone in it.” He drew

his forefinger along her neck and traced the turn of her throat with his

fingertips, following the line along her collarbone. “I should be a selfish

brute to take you from this place, for there should be no rescue. There would

be only the cruelty of plucking a rare bird from her nest to convey her to a

nautical cage.”

“I could never love the sea as you do, milado,”

said she softly, with a pining air.

“Never,

inpala. Your hair would be a hideous litch from the breeze, and your complexion

would be a coriaceous wreck, and I should never have you lose your looks

because of something I compelled you to do. Appearances are never important

until we ruin them, and I should never be so savage against such an exquisite

landscape.”

He

studied her expression in silence, and the pangs of parting soon supplanted all

their happiness. Evening always brought about his leave, and though he must go,

and she had borne the agonies of separation many times before, there was no reasoning

them away; the longer he stayed, the more impossible it was to part, and while

it was a pain not unfamiliar to her, she could never reconcile herself to it.

It was a perpetual vexation, one that must be suffered again and again, despite

her exultation when he was near. Wretched

adoration. Why must she love him, and why must he lavish her with all the

unmitigated attention that their attachment to one another deserved? It was a

cruel trick, a lark of the most vicious kind, that nature should always

contrive to keep them apart, that he must be to to sail the seas and she must

be repelled by them. Her illness aboard vessels prevented her from ever going

from land again, and though she tried to get the better of her ailments for the

sake of one day going abroad, her wellbeing compelled her to stay. She could never go with him; Marridon

was her home, and her duty to her many loyal subjects at the teahouse would

keep her there for as long as good business permitted. Should she have someone

to leave the teahouse to, should she have a daughter or even a sibling, to care

for the Cipher, she would be more inclined to ignore her illness for the sake

of flying with him, but the captain was the only one in the world she could

consider as lover, and the captain was not a man to be kept by children. She

would ask him to stay, but it would be cruelty to keep a nautivagant captain

from his domain, and with such a ship and such a crew, it would be taking him

from the home he had made for himself after being forced to quit the one he was

born to. If he could not be a lord in Lucentia, he should never be a lord in

Marridon; there were too many in Marridon’s first circles who would disdain him

for his heritage, and though Marridon was a moderate kingdom upon the whole,

the nobility, a class to which Danaco naturally belonged, would never admit a foreigner amongst them, reguardless his parents’ connections. Gentry,

regardless of realm, were more interested in situation, and Lord Danaco

Divelima had been expelled from Lucentia, a sin that might have been forigiven

had he never taken up a profession, and that

done by any man of half his rank was an unpardonable disgrace. To be

distinguished as a Captain of a ship was respectable in its way, but as a

captain of the navy, with uniform and distinction to add to his claims, and

Danaco would never join the king’s service. He liked to go his own way, as any

Lucentian far from home should do, and she could not command his predilections,

though her heart would readily obey his, if her health and situation allowed.

Being a lady of some consqeuence in Marridon was rather a blight than a

benediction by any stamp; the women that made up Marridon’s gentry could never

go where they liked, as many places were considered unfit for ladies, and a few

minutes spent near a stews or even a watering place without the accompaniment

of gentlemen would weave tales in the mouths of idle gossips, but being a rover,

being the looking-piece of a Lucentian captain, was a sin of the first order.

The civilities owed to a lady of quality in Marridon should be gone forever,

she should be abandoned by all her better connections, and the matron sighed

over the destiny of ladies in good society, whose moral judgement led them to

love unabashedly and whose depravity led them to pay for it.

Comments

Post a Comment