Story for the Day: The Hole in the Deck

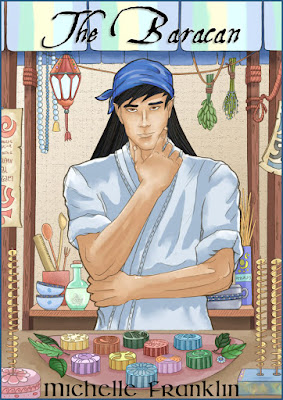

We have two new books coming out in October: The Ship's Crew, the third in the Marridon novellas featuring Danaco, Bartleby, and Rannig, and I Hate Summer, a side project I have been doing about my abhorrence for the past season. If you have not read The Baracan, the second in the Marridon series, it is now on sale HERE, and at all major online retailers. So much writing to finish, so little time...

|

| Read an excerpt of the Baracan HERE |

The rest of the evening passed agreeably: the crew had their

games on the main deck, resigning

themselves to Sirs and dice now that dancing

was out, those who would go ashore to enjoy the dining halls and tea houses went

after their matches were lost, and those who remained either took themselves

off to an early rest or remained with the musicians, to sing out the remainder

of the evening by way of a few round songs, calling out verses in melodic

dissonance, singing the history of Good Marrie the Whore and though there were

“Ten hands in her purse, there was still room for one more!” Bartleby, clinging

to his leaf flute, was still raving about the destiny of his poor bedchamber—and

he was sure he did not care about how many hands Marrie had tucked away in her

purse—Rannig, together with Ujaro and Brogan, was mending the deck under

Bartleby’s watchful eye, and Captain Danaco was standing by, joining the dice

game and throwing in another mark to the betting pool.

“Five

to start and ten more after you roll your first die, Shanyi,” the captain

declared. “There’s for your roll, and you had better roll above a three, and

that is all.”

Shanyi

blew on the dice. “I will do my best, captain, but you know how odds go.”

“I know

someone who should tell you to hang your odds.”

Here

was a sagacious look, and everyone in the dice game made a sly glance at

Bartleby, who was invigilating the reconstruction of the deck with feverish

animation.

“What

are you doing there with that beam?” the old man frothed, glaring violently at

the top of Brogan’s head. “And why do you have a sanding stone in your hand?

“Roundin’

the edges o’ the board,” said the top of Brogan’s head, his copper hair bobbing

up and down through the hole in the deck. “Gotta shave ‘em down a bit so’s I

can slot it in to joint. I don’t round ‘em down, they won’t fit proper.”

“Properly,

you barleychild,” said Bartleby sharply. “Properly. If I am going to be made to

listen to your agronomist cant all evening, I will have you speak properly.”

Brogan’s

head vanished momentarily. “That a fancy werd fer a famrer?” he murmured to

someone below him.

There

was a short silence, and then, after a few shrugs and some musing, Ujaro’s

voice said, “I suppose so, in that context.”

“Ain’t

no harm in bein’ a farmer, auljin,” said Brogan presently, the top of his head

returning to the hole. “My talkin’s what it is. Only learned it from the farms

‘cause I grew up on ‘em. Sure, everyone talks like this where I’m from. I sound

just fine to me. Yer the one with the funny accent.”

Bartleby

snuffed. “I, the one with the accent? Ha! I learned how to speak properly from

first-rate masters at the Academy, you soilspawn. You learned your elocution

from a potato patch.”

“Pretty

sharp patch, then, ‘cause it musta taught me to read and write too.”

A

whisper from the hole quietly begged Brogan not to agitate the old man, but it

was far too late for warnings; Bartleby was in the first ardours of a capital

rant, his nostrils throbbing and furnishings standing at attention, the

exsibilations of air being hissed through clenched teeth the overture of the grand

display.

“Listen

here to me, you sullied pea-poddy,” Bartleby raged, his fists shaking at his

sides in strained fury. “You will fix the hole that you and the boy have made

in the deck, and you will do it without noise and without remonstration. Nobody

wants to hear your farmstead bibble-babble or anything else you have to say—nobody!--

so be quiet and finish your work without comment.” Brogan was about to say that

he was being quiet when Bartleby had asked him a question, prompting him to

speak, when the old man continued with, “--And if I hear one word out of

turn—one word about my being the one who has the barbarous drite of an accent--

I will wait until you and your pillowpartner are in the violent throes of flesh-frotting

one another and have you tarred together!”

There

was a pause. Brogan’s hair flounced as sounds of subdued mirth echoed from

below.

“What

are you sniggering at?” Bartleby demanded, his whiskers bristling.

Brogan’s

hair jostled as he laughed. “Yer actin’ like we wouldn’t like bein’ stuck

together.”

“Yes,

well,” Bartleby sniffed. “You make a very good show of your affection—no, don’t

mouth-maul him now! There is a hole to fix—“ There was a strange pause, and the

tops of two heads below turned toward Bartleby to give him a chary look. “—Hang

your insinuations! You know very well what I meant. Do not twist my meaning,

however you might confuse it. No one is amused with your fledgling japes, no

one at all, so you may stop laughing this moment and continue fixing the deck

you broke. Get on with rounding your planks or whatever it is you were doing

and mend this monstrosity. I want it done before nightfall. My bedtime is coming

on— gah!“

A hand

emerged from the hole, and it gripped the front of Bartleby’s hat and pulled it

down over his eyes.

“He is mauling me, captain!” Bartleby wailed,

pulling up his hat and failing about. “The southern savage is absolutely

mauling me!”

“What

is happening there?” Danaco called out, looking over from across the deck.

“Brogan, are you slashing the old man?”

Brogan’s

head emerged from the hole. “Just pulled his hat down so’s he’d hush up his

racket, cap’n.”

“He

will make a noise, I grant you, Brogan, but ripe old date-palms will rattle

louder when agitated.”

“He

abused me, captain!” Bartebly cried, stabbing a finger at Brogan’s head. “Did

you see how this barm-barbarian lunged at me and glaumed my hat?”

“He did

not hurt you, surely. He has only ruffled your feathers, my little cucubate,

that is all. Well done, Shanyi. I needed those twos for my score. Now a seven,

if you please, and I will not take anything less than that.”

The

captain turned back to his dice game, and Bartleby gave a firm tut.

“A man

does not touch another man’s hat,” Bartleby grumbled, rearranding the sit of

his hat. “It not done. It is scandalous to touch what another man wears on his

head.”

“Dangerous

too,” said Brogan’s voice, from the hole. “Now my fingers smell like dead

moths.”

Bartleby

snarled and his wrinkles crimsoned. “There’s for your ruffled feathers,” he

hissed, kicking his foot at Brogan. “You see how this cumbering smatchet speaks

to his elders, captain? And you still have not punished him for manipulating

me.”

“You

will please not to be so severe on my carpenter, Bartleby,” said the captain,

looking over again from his dice game. “He has not hurt you, surely. Brogan is

all love and milkiness, as most Frewyns are. Where has he hurt you? I see no

marks on you, and I shall not dissemble and say I see them.”

“But he

has hurt my feelings, captain,” Bartleby avowed, his hands trembling in violent

agony. “My feelings!”

“Well,

he does no wrong there. You feelings are so easily injured, my old friend, I

should wonder how they have not died long ago. Shanyi, man, what do you do

there with those dice? Did not I tell you I need a seven to win? And here you

have rolled a five.”

“I am

sorry, sir,” said Shanyi, who was sitting by his knee, “but despite what we all

might like, I cannot roll twos and sevens every time.”

“You

can very well with Feiza’s dice.”

“Yes,

sir, I can, but so can anyone who uses Feiza’s dice.”

“Quite

so,” said the captain, smiling.

Feiza

protested against having any such designedly surreptitious dice, and if his

dice did roll sevens every time, it was no more than they were meant to do,

for, as Feiza reminded the party, “It weren’t right to be tellin’ the dice how

to roll ‘emselves, if they’re wantin’ to roll a seven or a two, sure’n us’nt

gonna tell ‘em what to do.”

He made

a firm pout and pretended to be morally wounded, but wry glances went round the

party, and while Feiza was flurning and petting his slighted dice, which he was

disallowed using in the current game, the captain was exchanging smiles with

the rest of his men, all of them inclined to admit that while the challenge of

a game of chance always held a charm for them, the powers of Feiza’s dice were

sometimes welcome.

“Very

well,” said the captain, “I will not cheat when there is anything like a wager

on the table. Here’s for the pot,“ putting a few gold coins down, “and you will

roll a seven this time, or I will have the tatti-pratti man peel you and put

you in his vats.”

Shanyi

held the dice in his hand on considered this. “Well, I would be rather crisp

after a good fry.”

“Go on,

man, and throw the dice,” the captain laughed, “and we shall see whether you

end up peeled and pobbled.”

The

dice game went on, sevens were rolled, and another winning combination brought about

regales and gapes as Brogan and Ujaro continued their work on the hole in the

deck. Bartleby still mantled over them, investigating their progress with a suspicious

eye, and Rannig soon joined them, to bring round their evening tea and help

mend the hole he had made. He came from the galley by way of the dice game, to see

whether anyone should like their evening cup, and after approaching the hole

and giving the last two cups to Brogan and Ujaro, Rannig lay his trey aside and

climbed down the hole, to continue the work that Brogan had begun on the

planks.

Comments

Post a Comment